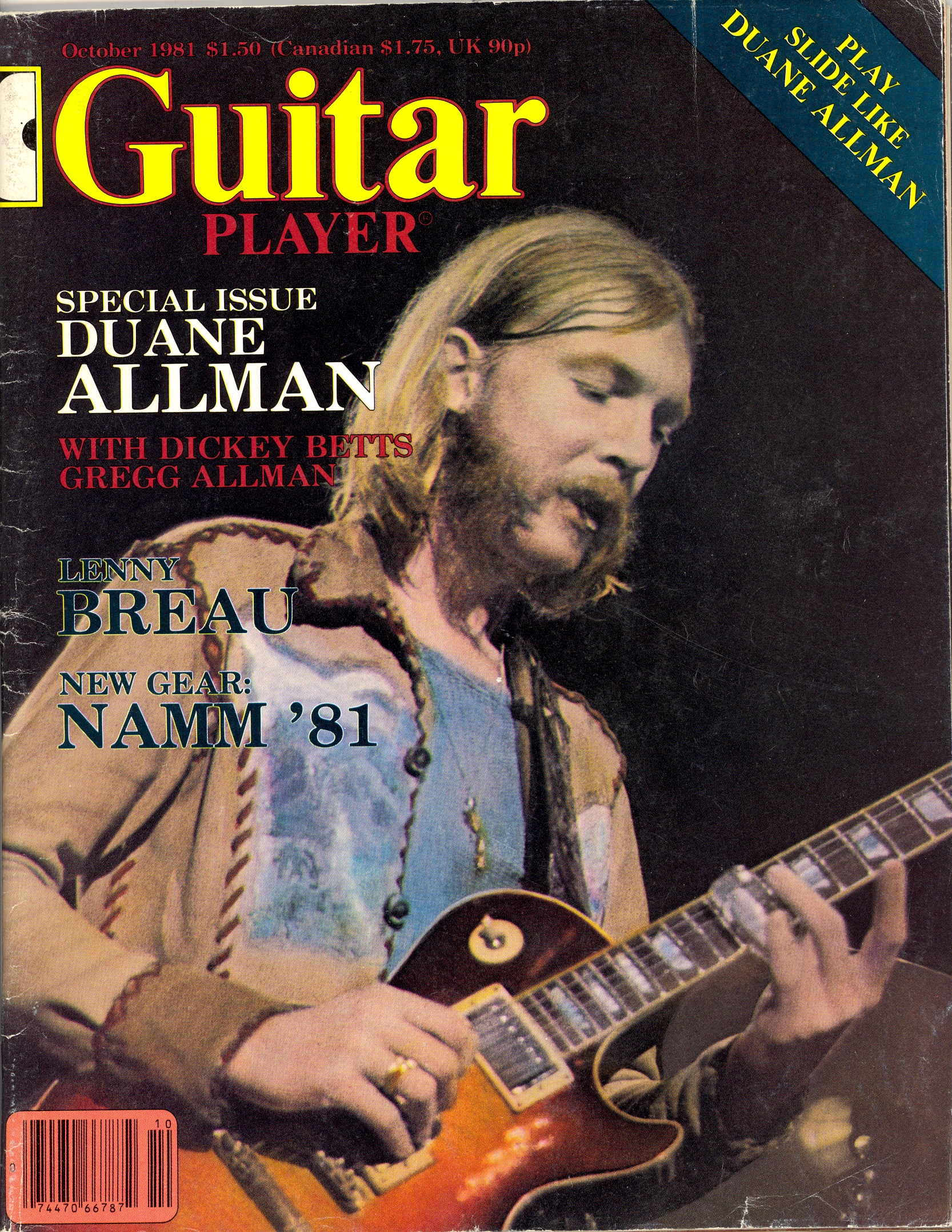

Duane Allman- (1946-1971) Guitar Player Magazine Article from October 1981

CLICK ON THE FOLLOWING LINK TO SEE BEN UPHAM’S ROCK MUSICIAN ARTWORK:

Rock Art by Ben Upham

CLICK ON THE FOLLOWING LINK TO PURCHASE DUANE ALLMAN MUSIC:

PURCHASE DUANE ALLMAN MUSIC

Duane Allman (1946-1971)

by Jas Obrecht

Guitar Player Magazine

October 1981

During an amazingly fertile five-year recording career, Duane Allman metamorphosed from a teenager struggling for a psychedelic sound to the foremost slide guitarist of the day. Ten years later, the importance of his greatest work, the Allman Brothers Band’s classic At Fillmore East and Eat A Peach, Derek & The Dominos’ Layla, and a handful of studio R&B and rock tracks-remains undiminished. Duane mastered bottleneck guitar as no one had before, applying it to blues and taking it to a very melodic, freeform context. He brought the style new freedom and elegance, and for many he is still considered the source for blues/ rock slide.

As the founding and spiritual father of the Allman Brothers Band-surely one of the best rock acts of the era- Duane became the figurehead of a musical style known as “the sound of the South.” With the Allman Brothers, he carried a deep-felt love for his native music-especially that of black bluesmen-to a rock audience, just as British guitarists had a few years earlier. Having learned his blues-based playing first-hand in the South, Duane had a more authentic feel than many contemporaries who had learned only through records. With co-lead Dickey Betts, Allman also helped popularize the use of melodic twin-guitar harmony and counterpoint lines.

Fortunately, Duane’s playing is documented on close to 40 albums, many of these studio projects done as lead guitarist for the Muscle Shoals rhythm section. As a sideman, Allman added a compelling, natural feel and distinctiveness to whatever he played on. (A good sampling of his studio work was released by Capricorn as Duane Allman: An Anthology and An Anthology, Vol. Il.) According to Jerry Wexler, who as VP for Atlantic Records used Duane on many sessions, “He was a complete guitar player. He could give you whatever you needed. He could do everything-play rhythm, lead, blues, slide, bossa-nova, with a jazz feeling, beautiful light acoustic-and on slide he got the touch. A lot of slide players sound sour. To get clear intonation with the right over-tones-that’s the mark of genius. Duane is one of the greatest guitar players I ever knew. He was one of the very few who could hold his own with the best of the black blues players, and there are very few-you can count them on the fingers of one hand if you’ve got three fingers missing.”

Friends describe Duane as an inspiration, a proud, likable man whose presence immediately drew attention and whose artistry profoundly influenced those who worked with him. He was an original, as unafraid to take chances onstage as he was in other sides of his life. By all accounts, he lived for music and the pleasure his playing brought people. During the ten years since his tragic death at 24, Duane has become one of the legends of guitar.

Howard Duane Allman was born in Nashville, Tennessee, on November 20, 1946. His only sibling, Gregg, was born a year later. Their father was killed while they were young, and the boys were raised by their mother, Geraldine. They attended Castle Heights Military School in Lebanori, Tennessee, where they briefly studied trumpet. In hopes of finding better work, their mother moved the family to Daytona Beach, Florida, in 1957. In 1960 Gregg saved up and bought himself an acoustic guitar. Soon afterwards, Duane got his first motorcycle. “A Harley 165,” he told Tony Glover in an interview printed in An Anthology. “Ring-ding-ding-ding; had a big buddy seat, would do 50 miles an hour-boy, I had a great time with it! I still got that motorcycle jones on me, I can’t get away from that. Anyway, I tore up the bike and Gregg learned to play the guitar. I traded the wrecked parts for another guitar, and he taught me. Then it’s just apprenticeship, your regular old thing-you play for whoever will listen and build them chops, build them chops.”

Duane quit high school to stay home and practice on his new Gibson Les Paul Junior, often jamming with his pal Jim Shepley. By then, Allman was sure that playing would be his life. He later told interviewer Ed Shane for a Capricorn promo album called Duane Allman Dialogues: “There’s a lot of different forms of communication, but music is absolutely the purest one, man. You can’t hurt anybody with music. You can maybe offend somebody with songs and words, but you can’t offend anybody with music-it’s just all good. There’s nothing at all that could ever be bad about music, about playing it. It’s a wonderful thing, a grace.”

Duane listened to Robert Johnson, Kenny Burrell, and Chuck Berry albums during the day, and at night switched on R&B radio stations for further inspiration. He Was influenced by Jeff Beck’s playing with the Yardbirds, and always had a special affinity for B.B. King: “He can do anything! He could sing ‘Happy Birthday’ and bring tears to your eyes.” At the time of the Layla sessions, he told an interviewer that Eric C]apton “wrote the book, man-The Contemporary White Blues Guitar, Volume 1. His style and technique is what’s really amazing. He’s got a lot to say, and the way he says it just knocks me out.” Later Duane came to especially appreciate jazz horn players, claiming: “Miles Davis does the best job, to me, of portraying the innermost, subtlest, softest feelings in the human psyche. He does it beautifully. John Coltrane, probably one of the finest, most accomplished tenor players, took his music farther than anybody I believe I ever heard.”

The Allman brothers’ first gigs were at a local YMCA, covering Chuck Berry and Hank Ballard & The Midnighters tunes. Although it was uncommon at that time for white and black musicians in Florida to mix, Duane and Gregg then joined the House Rockers, the rhythm section for a black group called the Untils. Duane remembered, “We were a smokin’ band! Boy, I mean, we would set fire to a building in a second. We were just up there blowing as funky as we pleased; 16 years old, $41 a week-big time. And all we wanted was to hear that damn music bein’stomped out. That’s what I love man, to hear that backbeat popping, that damn bass plonkin’ down, man. Jesus God!”

Gregg graduated from high school in 1965, and the brothers formed a band called the Allman Joys. They loaded up a station wagon and began touring the southern roadhouse and bar circuit. At best, things were stormy at first as they threatened to break up several times. Then the Joys began getting all the work they could handle-six shows a night, seven days a week-and discovered they loved the energy of the stage.

After appearing at NashVille’s Briar Patch Club in 1966, the Allman Joys were recorded by Buddy Killen and songwriter John Loudermilk. A pulsing version of “Spoonful,” complete with organ and reverb-heavy, psychedelic guitar licks, was released as a 45 and sold well regionally. Other tracks from the Nashville session were issued in 1973 by Dial Records as Early Allman. “Doctor Fone Bone” showed the influence of their early days backing R&B acts, and the fuzzy solos in “Gotta Get Away” and “Bell Bottdm Britches” briefly hinted at Duane’s future style. Even on these first recordings Gregg sang with a smoky, black-sounding voice that the liner notes declared “anguished, world weary.” Still, they were searching for a sound, and there was little hint of a future guitar star in their midst. Duane was to progress a long way in the next five years.

The original Allman Joys fell apart in St. Louis in 1967, and Duane and Gregg formed a lineup with drummer Johnny Sandlin and keyboardist Paul Hornsby. At first they used the name Allman Joys, then Almanac. While appearing in St. Louis in 1968, they were spotted by a manager who told them they could make it nationally if they went to California. The group moved to LA and signed with Liberty Records, who renamed them Hour Glass. By Gregg’s account, this was one of the low points of the brothers’ careers. There were plenty of clubs in the city’s burgeoning rock scene, but the label would selddom allow them to perform in public. The musicians had little income.

For the cover photo of their debut Hour Glass album, the group was taken to a costume shop and dressed in fancy, pre-20th century outfits. The liner notes described the music within as “Psychotic phenomenon, from rhythm and blues to driving psychedelic beats. And soul…reeking of soul.” At best, Hour Glass was miscast in image and material. Most of the smooth, superficial album consisted of over-produced, pop-vocal tunes, complete with overpowering horns and backup singers. Although writing songs then, Gregg managed to include only a remake of “Gotta Get Away” on the first album. “A good damn band of misled cats was what it was,” Duane told Tony Glover. “They’d send in a box of demos and say, ‘Okay, pick out your next LP.’ We tried to tell them that wasn’t where we were at, but then they got tough: ‘You gotta have an album, man. Don’t buck the system-just pick it out!’ So okay, we were game. We tried it-figured maybe we could squeeze an ounce or two of good out of this crap. We squeezed and squeezed, but we were squeezing rock. Those albums are very depressing for me to listen to-it’s cats tryin’ to get off on things that cannot be gotten off on.” Duane’s solos were fairly primitive and mixed to the background.

On the band’s second release; Power Of Love, the horns were mercifully gone, and Pete Carr had replaced the original bassist. For the first time Duane began to step out with supple rhythm grooves and several interesting, fuzz-heavy solos. He added B.B. King-style licks to “I’m Hanging Up My Heart For You,” and appeared on electric sitar on “Norwegian Wood.”

In April ’68 the Hour Glass drove to Fame Recording Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where, without interference from slick LA producers, they could lay down blues tracks. With Jimmy Johnson at the controls, Duane opened up as never before- fluid, raw-toned, and emotionaL Hour Glass’ “B.B. King Medley” (chosen to open An Anthology) contained the first prime examples of his expressive blues style. The unmistakable Allman touch had finally been captured on tape. The group took the demos to their West Coast manager, who said they were “terrible and useless.”

Hour Glass returned to the South and drifted apart after a few engagements. Duane and Gregg jammed with various bands and worked as paid sidemen on an album their drummer friend Butch Trucks was cutting with 31st Of February. The original project was never released, although nine poorly-recorded 31st Of February outtakes with Gregg singing were released by Bold Records as Duane & Greg Allman. Of special interest here is the only legally-released version of “Melissa” featuring Duane, one of his earliest recordings with a bottleneck. Even then his slide parts were lyrical, clearly enunciated, and sophisticated.

Gregg went back to LA in 1968 to fulfill contractual agreements with Liberty, and Duane started jamming in Jacksonville with bassist Berry Oakley, who was in a lineup with Dickey Betts called The Second Coming. He moved in with Oakley until Fame owner Rick Hall, remembering the Hour Glass dates, sent him a telegram inviting him to participate in Wilson Pickett’s November ’68 sessions. Allman came up, and suggested that Pickett sing “Hey Jude,” which eventually became the LP’s title track and sold a million singles. According to Wexler, Duane’s contributions to the tune were a dazzling departure from the usual R&B sound. The guitarist also splashed effecient blues solos on “Toe Hold” and “My Own Style Of Loving.” Pickett’s “Born To Be Wild” put his psychedelic training to good use.

The Muscle Shoals rhythm section loved Allman’s authentic country funk and blues playing, and invited him to become their staff lead guitarist. Duane signed a contract with Hall and moved up to Muscle Shoals, then a conservative town of 4,000 where you couldn’t even buy a beer. The new musician in town was a striking sight with his long red hair, tie-dye shirts, jeans, and red-white-and-blue tennis shoes. For Duane, the first few months in Muscle Shoals brought well-needed peace. “I rented a cabin and lived alone on this lake,” he later remembered. “There were these big windows looking out over the water. I just sat and played to myself and got used to living without a bunch of that jive Hollywood crap in my head. It’s like I brought myself back to earth and came to life again, through that, and the sessions with good R&B players.”

In January ’69 Duane joined singer Aretha Franklin in New York to record This Girl’s In Love With You. He added a smoldering blues solo to “It Ain’t Fair, and his opening slide glissando established the whole tone of “The Weight. He also appeared on the singer’s Soul ’69 album and added a track to Spirit In The Dark. A month later he accompanied his friend King Curtis on the saxophonist’s Instant Groove album, and was the only sideman credited in the liner notes. Duane played at least four show-stopping solos on the LP, and by then his phrasing was honed considerably. He was back on electric sitar for Curtis’ “The Weight” and “Games People Play”, which won a Grammy that year for best R&B instrumental. Both tunes are on the Anthology albums. After a few months in Muscle Shoals, Al1man was asked by Hal1 if he wanted to try recording as a front man. In February, backed by Berry Oakley, Hornsby, and Sandlin, he recorded several tracks. Duane sang, proving to have a surprisingly gentle voice on “Goin’ Down Slow,”which is on An Anthology. Two other cuts, both on An Anthology: Vol. ll, show a penchant for humor: He galloped through Chuck Berry’s “No Money Down,” and sang an original called “Happily Married Man,” which is actually a tribute to being on the road and free from your spouse. The album was never completed, and Hall sold Duane’s contract to Atlantic VP Jerry Wexler. Later Wexler sold it to Otis Redding’s manager Phil Walden, who was assembling a roster for a new Atlantic specialty label called ‘Capricorn Records’.

Meanwhile, Duane was becoming increasingly disenchanted with studio life, as he explained to Ed Shane in Duane Allman Dialogues: “Studios-that’s a terrible thing, man! You just lay around and get your money. All of those studio cats I know, like one of them gets a color TV, see, and then the next day, man, they’re all down to Sears or wherever-‘Hey, I’d like to look at some color TVs.’ And like this one place I know, all these cats-five of them-had Oldsmobile 442s. One of them traded for a Toronado, and so all of them traded for Toronados. And now one of them’s got a Corvette, and now they’re all looking for new Vettes. Man, this is sickening. They’re just keeping up with the Joneses and not playing their music. I was down there for about a half year, and I got sick of it. The sessions I do now, I just go in there and do it and leave.”

During one of his occasional visits back to Jacksonville, Duane jammed with Betts, Oakley, Butch Trucks, and Jai Johanny Johanson, a drummer he met at Fame. Except for Gregg, these were all of the future members of the Allman Brothers Band. “We set up the equipment and whipped into a little jam,” Duane remembered. “It lasted two-and-a-half hours. When we finally quit, nobody ever said a word, man. Everybody was speechless. Nobody’d ever done anything like that before–‘:it really frightened the shit out of everybody. Right then I knew-I said, ‘Man, here it is!’ I told Rick I didn’t want to do session work full-time anymore. I had found what I really wanted to do.” On March 26, 1969, Duane called Gregg back from California. After years of disappointments, one-night stands, and studios, the Allman Brothers Band was born.

Despite the fact that he was the group’s founder and had a prior reputation, Duane insisted from the start that they were to be equals. They pooled their money and rented a house at 309 College Street in Macon, Georgia. They slept on six matresses Walden provided, and plowed all of their money back into the band. The musicians jammed together a lot, occasionally going to nearby Rose Hill cemetery to play acoustic guitar and write songs. In fact, reported Twiggs Lyndon, the band’s original road manager, most of the songs on the first Allman Brothers album were written at Rose Hill.

True to his plan, Duane returned to Muscle Shoals several times while the Allman Brothers were still rehearsing. Boz Scaggs, recorded in May ’69, was one of his finest early studio efforts. “Finding Her,” which contains some sophisticated slide, climaxes with Duane using his Coricidin bottle to produce the far-away bird sounds that later show up in “Layla,” “Mountain Jam,” and several other cuts. Other standout Allman tracks on the project are the raw, long-building solo in “Loan Me A Dime,” the pedal-steel effects in “Another Day,” and a few Dobro parts.

His next project was The Dynamic Clarence Carter (a misprint in An Anthology dates this session to 1967). For a studio blues player from the South, Carter’s “Road Of Love” was a perfect slide vehicle, and Duane cut through the horn’s funky groove with a fat, vocal tone. Later in the year Arthur Conley’s More Sweet Soul gave him the chance to blast blues licks through a quasi-Jamaican “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da.” He also lent funk rhythms and firey leads to “Stuff You Gotta Watch,” and a touch of slide to “Speak Her Name.”

Back on College Street, Betts and Allman were discovering that they brought out the best in each other as they worked delicate harmony and counterpoint lines into their jams. In September ’69 the band traveled to New York City and cut The Allman Brothers Band in two weeks. The album signalled a new direction in American rock and roll. Tight, danceable, and loaded with rhythm changes, the music clearly resulted from days of inspired jamming. Even from the start the massive guitar hooks opening “Don’t Want You No More”-Betts and Allman exploded the two-guitar band tradition of having one player relegated to rhythm while the other played lead. Instead, guitars were used for unison and counterpoint lines, and there was plenty of slide and innovative blues, with special attention to tone. Duane soared through “Dreams” with a lovely, melodic slide solo remarkable in its control and shifting tones. As Gregg and Dickey point out in their companion pieces, it’s one of the best recordings he made.

The Allman Brothers Band sold only moderately well, but Duane’s unshakable confidence kept them together. Over the next two years they played over 500 dates, usually traveling with 11 people in a Ford Econoline van. Within a short time, Johnny Sandlin reflected for An Anthology, “Duane was very well-known throughout the South as the guitar player. Every band had seen him; guitar players all watched him. He influenced a lot of people into playing their own thing instead of just being copy R&B bands. If he met other guitar players that he thought were promising, he’d either loan or give ’em a guitar, anything he could do to help.”

Johnny Jenkins’ October ’69 Ton-Ton Macoute! sessions reunited Duane with former Hour Glassers Carr and Hornsby. Duane played slide Dobro on “I Walk On Guilded Splinters” and a soulful, moving version of “Rollin’ Stone,” and electric slide on three other cuts. Jenkins’ “Dimples” contained Brothers-style twin lead guitars. In late November Allman also played slide and lead on four cuts on John Hammond’s Southern Fried. Of note here is the well-controlled bottleneck on “Shake For Me” and a swinging blues lead on “Cryin’For My Baby,” during which Duane used the theatrical technique of reaching behind his fretting hand to raise and lower the pitch of the string. In 1969 Duane also appeared on Otis Rush’s Mourning In The Morning, Barry Goldberg’s Two Jews Blues, and a Percy Sledge album. With Eddie Hinton on lead, he also cut the Atlantic single “Goin’Up The Country” as part of a studio lineup named The Duck And The Bear.

The Allman Brothers’ Idlewild South, recorded in Miami, New York, and Macon, marked the beginning of the band’s association with Tom Dowd, who also produced At Fillmore East, Eat A Peach, and Layla. Dickey and Duane continued to explore the use of guitars in harmony on “Revival,” “Leave My Blues At Home,”and Bett’s magnificent “In Memory Of Elizabeth Reed,” which is surely one of their best studio instrumentals. Using long-sustaining, sweeping tones, Duane turned in a masterful bottleneck performance in “Don’t keep me Wonderin’,” and the second Side ot the LP found the guitarists outshooting each other in a blues jam on Willie Dixon’s “Hoochie Coochie Man.”

After Idlewild South’s release, Duane told a radio interviewer that their strategy for the next recording would be different: “The stage is really our natural element. When bands start to play, they just play live. We haven’t got a lot of experience in making records. I do, a little bit, from doing sessions, but not like a polished session man or anything. We get kind of frustrated doing the records; so consequently our next album will be for the most part a live recording to get some of that natural fire on it. We have rough arrangements, layouts of the songs, and then the solos are entirely up to each member of the band, Some nights we are really good, and some nights ain’t too hot, you know. But the naturalness of a spur-of-the-moment type of thing is what I consider – the most valuable asset of our band. When you make records, you can’t just do it over and over if somebody makes a mistake. Plus, the pressure of machines and stuff in the studio makes you kind of nervous. So a live album, I’m sure, would probably be the best thing.”

The Allman Brothers were recorded live in April ’70 at Cincinnati’s Ludlow Garage, and a rare track of Duane singing “Dimples” is preserved on An Anthology, Vol. II. The Allman Brothers’ reputation for high-powered live shows began drawing larger and larger audiences, as did their free concerts on days off. As Duane philosophized, “Anytime you’re getting paid for something, you feel like you’re obligated to do so much. That’s why playing the park is such a good thing, because people don’t even expect you to be there. About the nicest way you can play is just for nothing. And it’s not really for nothing-it’s for your own personal satisfaction and other people’s, rather than for any kind of financial thing. A lot of bread hangs people up; they try too hard. You can either do something or you can try to do something. Whenever you’re trying to do something, you ain’t doing nothing.”

Over 1970’s Fourth Of July weekend, the Allman Brothers played a two-hour set for more than 200,000 wildly receptive spectators at the Second Annual Atlanta International Pop Festival. Duane belted out clean, aggressive slide that day, and “Statesboro Blues” and “Whipping Post” were chosen for Columbia’s Isle Qf Wight/Atlanta Pop Festival anthology. In studio projects around this time, Duane sat in on Ronnie Hawkins, laying down killer electric slide on Hawkins’ versions of “Matchbox” and “Who Do You Love,” and swapping Elmore James-style licks with King Bisquit Boy’s harmonica on “Down In The Alley.” He tracked acoustic bottleneck on Hawkins’ “One More Night.” Allman also added lead to the track “Beads Of Sweat” on Laura Nyro’s Christmas And The Beads Qf Sweat album, and to Lulu’s New Routes.

Later in July Duane began his three-album association with Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett. He recorded with them in Miami and New York for To Bonnie From Delaney, playing an incendiary electric slide solo on “Living On The Open Road.” He also added fine, old-timey acoustic to their “Medley,” which included snatches of “Come On In My Kitchen.” Duane recorded “Come On In My Kitchen” with them in 1971 for their Motel Shot album, and again for a New York radio show (this version appears on An Anthology, Vol. II). Motel Shot also featured some high-pitched electric slide on “Sing My Way Home,” and several fine acoustic slide solos in “Going Down The Road Feeling Bad.” His last project with the Bramletts, D&B Together, was released in 1972.

In the last 13 months of his life Duane recorded his most important work, including Derek & The Dominos’ Layla, the Allman Brothers’ At Fillmore East and Eat A Peach, and studio projects with Herbie Mann, Cowboy, Ronnie Hawkins, Delaney & Bonnie, and Sam Samudio. Derek & The Dominos was probably his favorite and most important studio project. He was invited to participate after Tom Dowd brought Eric Clapton to an Allman Brothers gig. As Duane later described, “I went down there to listen to them cut [Layla], that’s what I went for. And well, like he’d heard my playing and stuff, and he just greeted me like an old partner or something. He says, ‘Yeah, man, get out your guitar. We got to play!’ So I was just going to play on one or two, and then as we kept on going, it kept developing. Incidentally, on sides I, 2, 3, and 4, all the songs are right in the order they were cut from the first day through to ‘Layla’ and then ‘Thorn Tree. ‘I’m as proud of that as any albums that I’ve ever been on. I’m as satisfied with my work on that as I could possibly be.”

Layla proved to be the meeting of two kindred minds and 20 amazing fingers. Duane and Eric pushed each other to new levels, and Allman played the unbelievable slide solos in “Key To The Highway” and “Have You Ever Loved A Woman.” At the conclusion of “Layla,” he tracked a kind of bottleneck symphony that concluded with imitation bird sounds. Later Duane noted that Eric played some slide on the cut, too: “He gets more of an open, slidey sound. But here’s the way to really tell: He played the Fender, and I played the Gibson. The Fender is a little bit thinner and brighter, a sparkling sound, while the Gibson is just a full-tilt screech.”

Allman also added slide to “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down And Out” and “It’s Too Late.” On other cuts the guitarists jammed or played in harmony, reaching their highest peak in “Why Does Love Got To Be So Sad.” In addition, a lovely Clapton-Allman acoustic slide duet of the old blues tune “Mean Old World” is on An Anthology. After Layla was released, Duane toured with Derek & The Dominos for a few weeks. In his Guitar Player interview in 1976, Eric Clapton credited Duane with getting him interested in electric slide: “There were very few people playing electric slide that were doing anything new; it was just the Elmore James licks, and everyone knows those. No one was opening it up until Duane showed up and played in a completely different way. That sort of made me think about taking it up.”

On March 12 and 13, 1971, the Allman Brothers recorded live at the Fillmore East. When you combine At Fillmore East with the other tracks recorded those nights-Eat A Peach’s “Mountain Jam,” “One Way ‘Out,” and “Trouble No More,” and An Anthology’s “Don’t Keep Me Wonderin”‘-the Allman Brothers emerge as one of the finest live bands of rock and roll. There were no wasted words or notes, no pointless jams. Duane’s performances on “Statesboro Blues,” “Done Somebody Wrong,” “One Way Out,” “Trouble No More,” “Mountain Jam,” and “Don’t Keep Me Wonderin”‘set a still-unsurpassed standard for electric slide. His collaborations with Dickey Betts roared to life onstage with incredible power and emotion as they challenged and inspired each other. They gave commanding blues performances in “You Don’t Love Me” and “Stormy Monday,” and harmony guitar parts abounded in “Hot ‘Lanta,””Mountain Jam,” and “In Memory Of Elizabeth Reed.” Duane’s no-holds-barred solos in these latter two cuts are among the most inventive and creative of his recorded work. The band recorded at the Fillmore East again on June 27, 1971, and the cut “Midnight Rider” was issued on An Anthology, Vol. II.

Next to the two Allman Brothers LPs, Herbie Mann’s Push Push contains Duane’s finest electric performances of 1971. The flautist’s easy, jazzy grooves and open spaces allowed Duane to create free-form, well thought out solos. By now Duane was as comfortable in the studio with a Dobro as he was with an electric, and he added some excellent acoustic slide to Ronnie Hawkins’ The Hawk, especially on “Don’t Tell Me Your Troubles,” “Patricia,” and “Odessa.” Late in his career Duane played Dobro on Sam Samudio’s Sam-Hard & Heavy, and reportedly appeared on the Everly Brothers’ The Stories We Could Tell. His last session as a sideman was with the laid-back Capricorn band Cowboy, playing slide Dobro on “Please Be With Me.”

In addition to the Fillmore material, Duane completed three studio cuts for Eat A Peach: a slide tune called “Stand Back,” a touching acoustic duet with Dickey Betts called “Little Martha” (the only original tune Duane recorded with the Allman Brothers), and “Blue Sky,” the rippling guitar harmonies of which are among the best the group ever recorded.

During the Eat A Peach sessions, Duane was asked by Ed Shane to express his thoughts on rock and roll: “Everybody is expending all this energy in various ways to get the same old feeling out of it that Little Richard can get in five minutes. And people are finally waking up to the fact that you can get as much of a good feeling out of a simple thing as you can out of something that’s hard. A lot of people who would have you believe they are intelligent musicians are playing bullshit. Music’s become so intellectualized. Man, music is fun. It’s not supposed to be any heavy, deep intense thing-especially not rock music, man. That’s to set you free! Anybody that ever listened to Chuck Berry or any of them cats knows that…. Rock is like a newspaper for people that can’t read. Rock and roll will tell you where everything is at. It’s something to move your feet and move your heart and make you feel good inside. You know, forget about all the bullshit that’s going on for a while, fill up some of the dead spaces.”

With At Fillmore East rapidly becoming a hit album and two years of touring behind them, the Allman Brothers Band decided in late October to take a few weeks’ vacation. Duane journeyed from Miami to New York City, where he visited his friend John Hammond. He then returned home to Macon, where, on October 29, 1971, he went to Berry Oakley’s house to wish the bassist’s wife a happy birthday. After leaving the house about 5:45 PM, he swerved his motorcyle to avoid hitting a truck that pulled out in front of him. The cycle skidded and turned, pinning him underneath. He died after three hours of emergency surgery at Macon Medical Center. Duane was 24.

The rest of the Allman Brothers Band played at the funeral in Macon, with Dickey filling in Duane’s parts. Delaney Bramlett then led everyone in “Will The Circle Be Unbroken,” and Gregg Allman sang a final tribute. The band concluded the day with “Statesboro Blues.” Duane was buried at Macon’s Rose Hill Cemetery, where he had often gone to meditate and play acoustic guitar during the early days of the band. Berry Oakley, who died a year later in a remarkably similar accident, is buried nearby.

Some say that the best music Duane created was never recorded; it was born on-stage and forever given away. Or it was the old country blues songs he sang by himself in the still of the night. For those who missed those occasions, Duane will always live on in his records. In talking about records near the end of his life, Duane shared some last advice with his brother musicians: “Develop your talent, man, and leave the world something. Records are really gifts from people. To think that an artist would love you enough to share his music with anyone is a beautiful thing.”

also:

musicians art

and:

rock art art

and

rock and roll art

and

rock and roll framed prints